Visual Art Tests the Limits of Language in Bowdoin Museum’s Turn of Phrase

Bowdoin Museum’s exhibition Turn of Phrase: Language and Translation in Global Contemporary Art, on view through June 4, turns our attention to the use of text in 20 works of art from the 1980’s to the present. Each of the exhibition’s three sections offers its own examination of written language’s capacity to define and connect our experiences, as well as its limitations in doing so. The included works put pressure on texts' perceived stability by using visual art to turn intended meaning on its head.

The first section, “Citations and the Politics of Legibility / Visibility,” considers what remains hidden even with the use of a tool as explicit as language. In most cases we accept that words are our most straightforward path toward understanding. In her wonderful accompanying essay, “Seeking Language(s) in Global Contemporary Art,” the shows curator, Sabrina Lin, Curatorial Assistant and Manager of Student Programs at BCMA, tells us of her own relationship to cross-cultural communication as “a Chinese speaker, an English writer, and a scholar of Italian literature,”¹ and points the viewer toward the difficulty at achieving a universal understanding.

Lin puts the theory of universality to task with Barbara Kruger’s, Untitled (We will no longer be seen and not heard), a series of cherry red-framed lithographs each borrowing from the visual language of 1950’s consumerism and a well-worn English idiom of the era, “Children should be seen and not heard”. Kruger alters the message to include herself in a campaign against the silencing. However, despite Kruger’s best efforts at being explicit, the full extent of the work’s intention might only be appreciated by a native speaker of English. In the same section we see Untitled (Crowd/The Fire Next Time) by Glenn Ligon, coal crystal lettering stenciled over a black and white photograph of the Million Man March. The artist cites James Baldwin’s 1963 essay, “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind,” creating a tension between the text and the underlying image of the 1995 march, which undermined Baldwin’s message of inclusivity in its exclusion of women and members of the LGBTQ community. Both text and image obscure the other, yet compel the viewer’s eye to allow both to exist at the same time.

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (We will no longer be seen and not heard)

While Lin’s first section contemplates the limitations of language, conversely, the following section, “History and Systems of Representation,” looks at ways in which it endows. A museum label’s power is in its ability to place an artwork in relationship to the institution’s centered position. The tenderness and symbolism of an artwork is in many ways at the mercy of its label’s authoritative typeface, which acts as a northstar the viewer can look upon to be rescued from uncertainty and find rest on the shores of reason. This dynamic further sanctions the dominance of the institution.

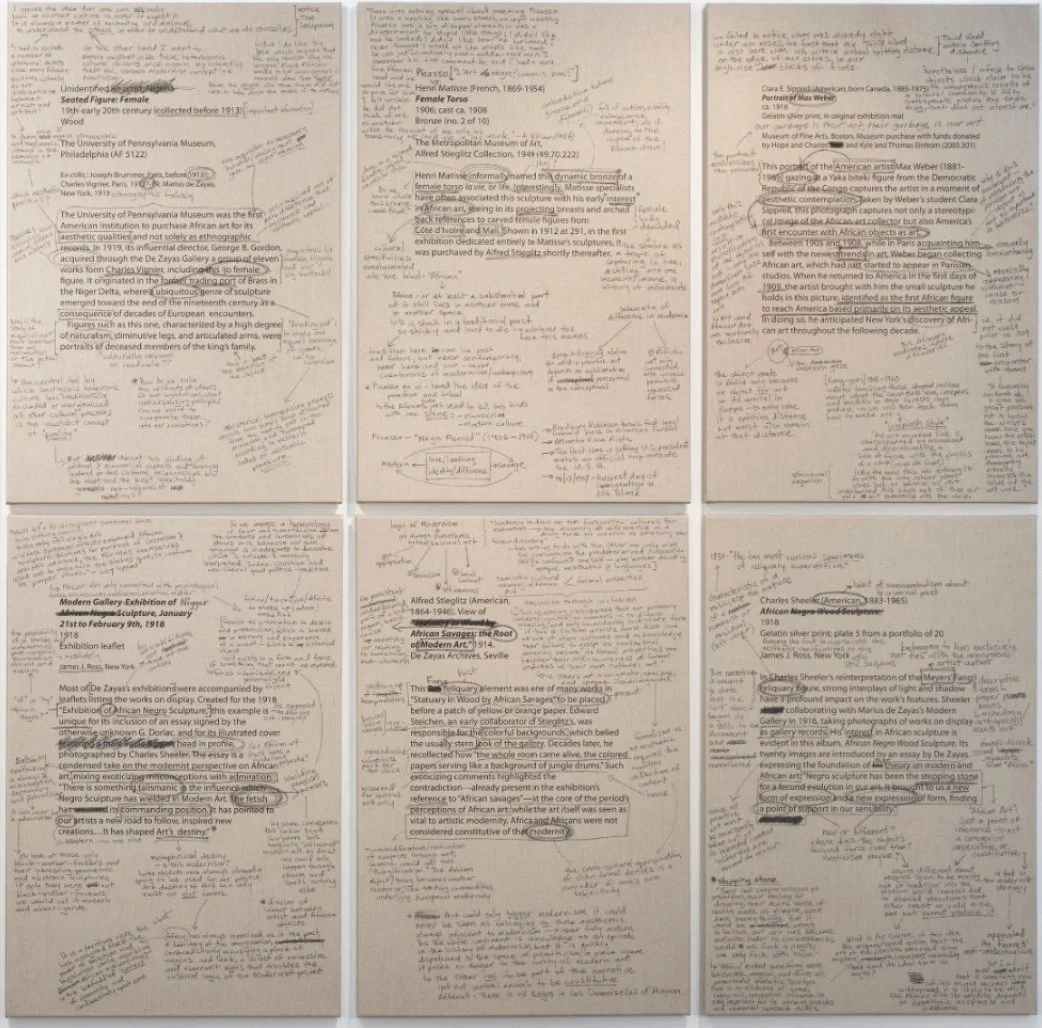

In Modern Art: The Root of African Savages, artist Meleko Mokgosi studies the language of six museum labels embedded with eurocentric, colonial narratives that blow through each passage, like a wind which moves the world, invisibly, to its favor. On Alfred Steiglitz’s label for Statuary in Wood by African Savages, Mokgosi traps the last sentence in the black outline of his pen, “while art itself was seen as vital to artistic modernity, Africa and Africans were not considered constitutive of the modernity,” circling the last word over and over and anchoring it with the weight of its true meaning: “the cross-cultural appropriation of alien formal devices is a reminder of one’s own subjectivity.” Each label is printed on a linen-wrapped panel. The viewer might wonder what color, what shape and light might live there instead if Mokgosi was not given the task of itemizing the West’s chronic impulse to other and own.

Meleko Mokgosi, Modern Art: The Root of African Savages

Lorna Simpson, Waterbearer

In the third and final section, “Personal Dialects and Reading the Body,” we see a collection of works which uses the shared understanding of language as an invitation and opening through which the viewer can access the artists’ own personal narratives. Lorna Simpson’s Waterbearer is a highly contrasted black and white photograph of the back of a Black woman in a white dress who pours water from two containers, each held in the hand of an outstretched arm, a pose resembling the uneven scales of justice. A silver pitcher in her left arm weighs heavier than the plastic jug in her right, and pulls her body toward it. Her silver bracelet appears like an extension of the pitcher, as though she is cuffed to it. One realizes even once both containers are empty, the more expensive one will still be the heaviest to carry. Framed within a sheet of white, the photo rests on a shifting foundation of text that reads, “She saw him disappear by the river, they asked her to tell what happened, only to discount her memory.” The story, again, pulls in two directions; her experience and the refusal of others to believe it. Language, in this case, fails even if what it says is true.

The intrigue of this exhibition is in watching the artist allow to escape what language tries to define and hold. Language is not fixed; it will never capture as much as it would like to, any more than looking up allows us to see the entirety of the universe. But we try, we crane our necks at what is dazzling and insufficient.